Sometimes it's fun to look at a complex problem like the NBA's current tanking debate and treat it the same way we treat video games or logic puzzles. Everybody's solution sounds a lot more perfect when it's presented in the abstract, unfettered by pesky reality and all of its unintended consequences.

In truth, these are vexingly complicated questions, not to mention important ones. Landing (or not landing) a generational superstar can be the reason a franchise succeeds or fails, meaning that it's not an exaggeration to say that these NBA structures can impact local economies, job creation, housing markets and more.

All of that is to say that if we tinker with things, we had better guess right. The remedy can't be worse than the disease, but so many lottery reform proposals skip over fundamental questions. How important is it for long-term league health that talent be at least somewhat distributed across its member teams? Is the league better or worse when only a handful of teams/markets have an obvious path to relevance? What will happen to the league in the long term of certain markets simply don't have a way to add top talent? If you completely remove what many feel are faulty reward structures, will the resulting randomness create a better product, or just be flawed in its own ways?

Those are the questions that should bounce around our collective consciousness as we evaluate all of the different reform proposals. If we're honest, many of them fix nothing, and others could actually present more harm to the long-term health of the league and its teams than what's currently in place.

There are countless variations on the proposals we'll poke holes in below, but they tend to fall in two broad categories: ideas that seek to change the pressure points around tanking, and those that seek to eradicate them altogehter by radically changing the way talent is distributed.

A. Proposals that shift the threshold for who tanks and when

These seven ideas at least don't fundamentally change the competitive realities for small market teams... but it's also unclear if they do much more than encourage different teams to focus on draft odds over winning...

1. Further flattening

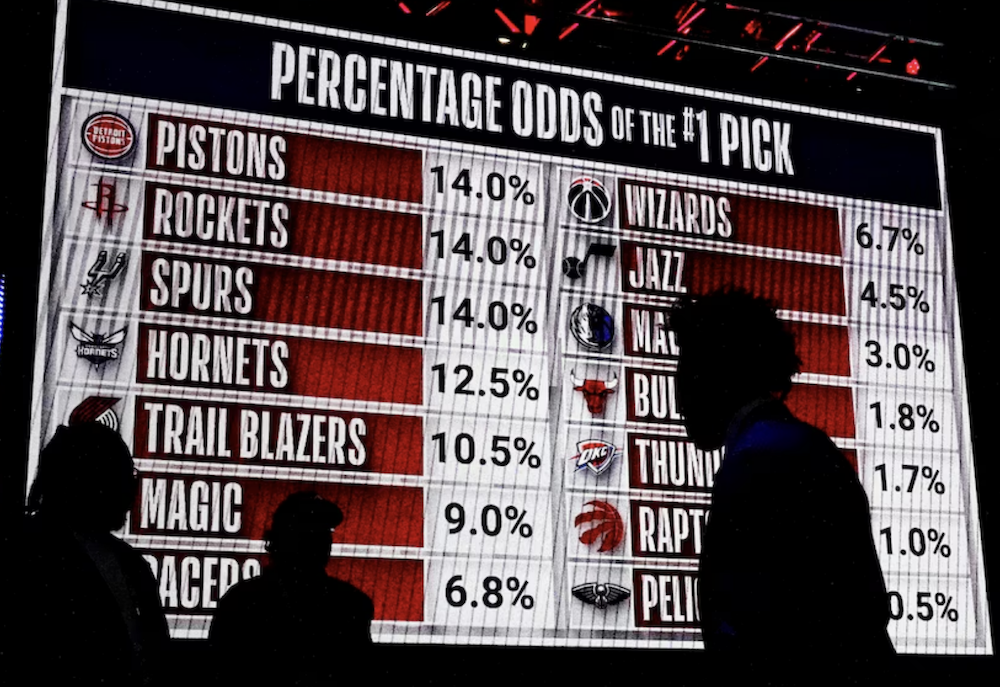

Why people think it would work: The idea here is to make it less of a straight line between "be really bad" and "get great pick." By increasing the element of chance, the thinking goes, we can dampen the incentives for teams to pull out all the stops. That's why the NBA flattened the odds before the 2019 draft, from 25-19.9-15.6-11.9-8.8 for the worst five teams to 14-14-14-12.5-10.5. Some people say the NBA should keep going down this path: if the odds for being the very worst are only slightly better than the odds for being fifth or sixth worst, maybe teams won't be as motivated to try to lose every game, the thinking goes.

Why it won't: If anything, the 2019 flattening has backfired. Fully a third of the league's teams are not trying to win right now, and we're in this position precisely because the NBA made it so more teams are compelled by the upside of losing. The Bulls are currently a game and a half outside of the Play-In, but just gutted their roster because if they can get to, say, eighth worst, they can have a not insignificant chance (26.2%) at a top-4 pick.

Flattening the odds will quite simply tempt more teams to tank. We're seeing proof of that every night.

The most extreme version of this is to go back to 14 envelopes in a big drum. But imagine would would happen in the play-if teams on the playoff cusp knew that missing out on the first round meant they could have a 7% shot at a Victor Wembanyama.

2a. Freeze lotto standings early

Why people think it would work: In this proposal, lottery standings are finalized at a speciic date: February 1, or the trade deadline, or the date teams were officially eliminated from playoff contention. This way teams with a talent deficit still have a way to access potential team-changing guys through a reverse-order lottery, but it makes March/April games less farcical because wins and losses after the ordained date don't have an impact on pick odds. Bad teams could spend the final two months of the season attempting to find some kind of momentum or identity to take into the next season.

Why it won't: Wouldn't teams still tank just as hard, only do it earlier to freeze their optimal draft position by whatever the date was? Wouldn't the optics be far worse if teams are fielding G-league lineups when there are still 50 games to go? If all you're doing is shifting the tanking problem earlier in the year, you're not really solving anything.

2b. Freeze lotto standings early + give credit for late wins

Why people think it would work: Like the option above, but in this case once you cross that magical line in the sand, wins actually count positively toward lottery odds. So if your team were 0-52 at the trade deadline and then 30-0 after, they would have the best chance at the #1 overall pick. More than just removing the motivation to be bad, this one actually rewards competence as the season goes along.

Why it won't: As with the above, teams will still tank hard early on. And especially in this revised scenario, schedule imbalance becomes a real problem. Schedule strength evens out over longer periods, but if we're only evaluating/rewarding teams based on their record after elimination, what if one team has a particularly tricky closing slate? Brooklyn's closing stretch, for example, has five home games against sub-500 teams (Sac, Cha, Atl, Was, Mil, Ind) before visiting Milwaukee and Toronto. Utah over those same two weeks faces the Cavs and Nuggets at home and also visits the Rockets, Thunder and Lakers. Is it fair if that two-week span on the calendar results in Brooklyn getting a higher pick?

This one would also punish teams with legitimate injuries. It does put some of the onus on teams to try to life themselves up by their own bootstraps before the help arrives from on high, but that might be tough for some teams to do. How long would Detroit have languished in 20-win territory before they finally lifted themselves into a spot where this proposed draft system could have finally helped them obtain a Cade Cunningham?

3. Limit consecutive lotto wins

Why people think it would work: There are different versions of this out there: some say a team that has won the #1 overall pick can't repeat for a number of years, other more stringent versions say that teams who were awarded any of the top four spots by ping pong balls are excluded from the next year's drawing. In any given season, it might reduce the number of teams who are playing roster games because the grand prize is not in play for everybody. But the real goal here is to dissuade teams from protracted rebuilds a la Sam Hinkie's "The Process."

Why it won't: There's enough support behind this one that it's likely some version of it passes. And it's not as offensive to small-market teams as others, but the main flaw here is the relative strength of drafts. If you win in the Zaccharie Risacher year but that means you're ineligible for the Cooper Flagg year, that's rough luck. Could teams opt to defer on #1 if it will keep them out of the next few lotteries? If you win the lottery with a traded pick, does that also disqualify you from next year's #1?

4. Flip lotto order

Why people think it would work: Instead of the worst non-playoff teams getting the highest lottery odds, give teams that barely missed the postseason the highest odds. This would theoretically force the most incompetent teams to claw their way to a certain level of competence, and bad teams would spend the final weeks of the season doing what basketball teams are ostensibly meant to do: try to win.

Why it won't: Most of the proposals that simply shift the tank incentives elsewhere aren't really solving anything. They're just moving the threshold for tanking. And if you think watching bad teams jockey for lottery position is a bad look for the NBA, imagine the PR crisis the league would face when teams are openly taking a dive in Play-In games. What do we expect a 9th seed to do if they know that winning two Play-In games earns them the privilege of getting demolished by OKC, and losing gets them a 14% chance at Cooper Flagg?? What an embarrassment that would be if such a team said "nah, we're good" and sat all of its starts for a Play-In game!

You could adjust by making lottery odds highest in the middle: say, the best odds for 6th through 9th worst, followed by 1st through 5th in some order and then keep the lowest odds for teams just outside the playoffs. But again, then you're just motivating teams to be the exact right amount of bad, and teams will be just as transparent about gaming that system. A tenth-worst team will suddenly start losing, but then as soon as they fell far enough, suddenly their best players would be healthy again and off minute limits. Maybe that's OK, but fans would definitely sniff out behavior that looks like the Incredibles racing meme.

5. Use 3-year records to calculate odds

Why people think it would work: The idea here is that 3-year cumulative records are going to be more stable and not as easily manipulated on any single night of basketball. Bad teams still wouldn't put the pedal all the way down, but it would be easier to forecast farther out, which might make teams less likely to jockey for every possible loss. And it still helps teams that are truly mired in a long-term talent shortage, as opposed to rewarding "gap year"-style tank jobs. If this year's lottery were decided that way, Washington would have the best odds, followed by Utah, Charlotte, Brooklyn and then Portland.

Why it won't: This wouldn't necessarily dissuade multi-year teardowns, and in fact sort of rewards them. It might improve the product on a given night, but might wind up consigning fans to years of following a team that only has the hope of getting hope. Rebuilds are long enough as it is.

6. Limit Pick Protections

Why people think it would work: Folks are quick to point out that three of this year's bottom six teams — Utah, Washington and now Indiana after giving a conditional pick in a midseason trade — are extra motivated to keep outstanding pick debts in the protected range. Would stricter rules about how picks can be protected in trades materially change Utah's and Washington's behavior?

Why it won't: Teams like Sacramento, Brooklyn, Dallas and now even Memphis appear plenty motivated to lose, and they own their picks outright. And while the WIz, Jazz and Pacers might be slightly more committed to their direction because of the "stick" of losing their picks, the "carrot" is plenty enticing on its own. I just doubt this is changing a ton of teams' behavior. Just guessing, but I'll wager that Utah's desire for a 27% chance at AJ Dybantsa, Darryn Peterson or Cam Boozer at least matches their fear of not having the pick at all.

B. Proposals that radically redefine talent distribution

Some people want to do more than shift the incentives; they want to completely blow up the way we think about talent distribution. These proposals are where you really have to ask yourself: how much will it hurt the NBA in the long run if we remove or complicate one of the few ways small market teams have to acquire top talent?

1a. The Wheel

Why people think it would work: Celtics executive Mike Zarren has pitched an idea to completely separate draft position from team record. In his proposal, draft order is set years in advance, with each team cycling through each draft spot over a 30-year period. Every team would be guaranteed to get a #1 pick no more and no less than once every 30 years. You'd also spread them out so that everybody picks in the top 10 every third year, and so forth.

Why it won't: Critics of this approach are quick to point out that we'd all invariably lose our minds when the randomness of the wheel gave us a year where a blue-chip prospect landed on a superteam. And that's true, that would lead to a lot of "why did we do this?!?" reactions. But that's not the worst outcome.

The worst outcome is when the most talented youngsters simply decided to delay coming out so they can land in their preferred spot. Remember, players can decide when they declare for the draft. If they knew precisely who would be picking at every selection years advance, they could completely game it out to land where they wanted. The NBA would have a huge problem the first time a Wemby-level prospect saw the draft board and said, "Hmm, Sacramento has the top pick this year and Miami will have it next year, I think I'll stay in school!"

There is already a natural ebb and flow to draft talent: some years the draft class is teeming with potential franchise changers, and some years you have an Anthony Bennett or Michael Olowokandi at the top. That alone is reason for teams to fear this arrangement: what if the one time in three decades your franchise gets that opportunity, it's an Andrea Bargnani year? But when you realize that players can (and almost certainly will) engineer things further to the detriment of non-glamour markets, it's hard to defend this one.

It would be bad enough if your team was stuck in the doldrums without a premium pick on the horizon for several years... but just imagine the gut punch to a franchise if they were about to get the #1 pick for the only time in three decades, and the top prospect said, "Nah."

It would change the value of draft picks as trade assets, too, which also hurts teams in search of marquee talent. Part of the reason "selling" teams will trade a star player for a pick-centered package is because of the upside play. If Memphis knew that that the picks they were being offered for Jaren Jackson Jr. were already determined to be 17, 13 and 24, do they do the deal? They could insist on other years, but the rules around trading picks in consecutive years make it hard to put together an a la carte package that would satisfy the seller without handcuffing the acquirer. So now we've made it harder for some teams to acquire stars through the draft AND through trades.

And it's not like this is a proposal the NBA could simply test our for a few years. Once you've committed to the idea, you have to follow through for 30 years (or 32, if the league expands) before you can ditch it without creating concerns around fairness.

1b. The Wheel Lottery

Why people think it would work: This variation on the idea above attempts to solve some of those flaws while still divorcing lottery odds from losses. In this one, teams take turns cycling not to specific draft spots, but in 5- or 6-team pods that take turns enjoying higher pick odds. So every five years, this group of six teams — some playoff teams and some not — gets 10% odds at the #1 pick. The next year they get 1% odds. The next year 3%. The next year 0%. The precise draft order is still determined by ping pong balls, but the underlying odds have nothing to do with your record.

Why it won't: Much of the same problems described above still exist, just with more randomness. A kick-ass team could still randomly land a #1 pick if it was their turn to be in the group with higher odds. A team that needs a talent injection could be years away from getting a solid chance at one, or could get the max odds in a year with a poor draft class.

With both of these wheel proposals, the deeper underlying question is: do we really want it to be THAT random? Or is the NBA healthier when the system gives non-competitive teams a slight nudge in the right direction? If Wemby doesn't go to San Antonio, if Cunningham doesn't go to Detroit... what ways do those teams have to ever climb out of the cellar? And more to the point: is it in the best interest of the 29 other teams to throw them a rope? One could argue that yes, the league is stronger when more fan bases have some basic level of hope and when talent isn't just falling into the laps of already elite teams.

2. Remove the draft altogether

Why people think it would work: Perhaps the most radical solution is to simply get rid of the draft. Let incoming rookies choose their teams like free agents do, and then there's no reason for teams to be bad.

Why it won't: This will be a blood issue for small market owners. Because it's not hard to see how this would play out: players will choose glamour markets, time and time and time again. Half of the league's markets would have almost no chance at landing a top young player, and this would also make it impossible for them to trade for stars since they don't even have draft picks to package.

Simply put, this would absolutely screw 20+ NBA teams, to the delight of the other 8-10.

Every smart agent would tell their client to get to a major market to cash in on bigger investments, and the rest of NBA cities would never see another Wemby-level talent again. But hey, buy your season tickets now to watch your team get crushed regularly by the handful of teams who are considered worthy ofhaving stars.

Remember when Kobe Bryant's agent bullied teams into letting his client fall all the way to 13th because Charlotte had a deal in place with the vaunted Lakers? Or how Ace Bailey's then representative tried to dissuade certain teams from drafting the Rutgers star so he could pick his landing spot? Those are all the evidence we need to conclude that a free agent system would favor the same markets over and over and over again.

A version of this proposal has teams still getting a draft "slot" with a salary exception proportional to their reverse order draft position. In other words, league-worst Sacramento could offer $15.2 million to their first-choice guy, but everybody else can only offer the salary slot that corresponds to where they would have picked, and the rookie free agent decides if he's going to chase the money or the market.

But how many rookies would choose Indiana's $11 million offer over the Clippers' $5.7 with all of the additional earning opportunities that come from residing in L.A.? And if the top 10 guys all tell Sacramento "no thanks," then do they still have to pay $15.2 million to 11th guy on their draft board? That's adding insult to injury: not only can those teams never add top talent, but they still have to pay a "small market tax" on the mid-tier talent they wind up with by default. Ouch.

So... what then?

Do we just give up entirely on improving the system?

Honestly... maybe?? The situation feels worse than usual right now for two key reasons: because this loaded draft class has an unusual number of teams foaming at the mouth, and because the flattened odds have allowed more teams to dream big. In a normal year, or if the league went back to the pre-2019 lottery system, there would still be a few teams prioritizing draft position, but nothing like we have today.

But the point here isn't necessarily that we should just shrug our shoulders at the problem and keep watching teams file 10-man injury reports. There are smaller tweaks, or even "lite" or blended versions of the concepts above that the NBA could try.

For example, what if instead of simply freezing lottery standings OR considering 3-year records, the league tried a hybrid of the two:

1. Determine lotto order by 70/30 ranking of reverse 3-year record up through trade deadline (70%) + win percentage thereafter (30%)

Could it work?: Teams could still try to tank in December and January to improve their odds, but because those 50-or-so games are weighted against the previous years' 164, it dampens the motivation to treat every game before the deadline like a must-lose.

And since teams should also want to be building momentum towards a competent post-deadline surge, maybe that would outweigh the tanking. Since those first 50 only account for about 23% of the record that will feed that 70% of the ranking (16% of the overall), a team's composite ranking would actually be helped more by winning games after the deadline that by sandbagging up until February, by almost double.

Or what if instead of fully reversing the lottery order and tempting fringe playoff teams with a reason to torpedo a .500ish squad, the NBA tried this:

2. Keep lotto order but with minimum qualifiers to access full odds

Could it work?: Keep the lottery order and percentages the same, but only teams within X games of the worst playoff team in both conferences enjoy their full odds.

Maybe a team that's more than 15 games behind that lowest playoff squad (currently Miami) gets half of their lottery combinations reassigned proportionally to the other lotto teams. Or if you're more than 20 back, you can't be awarded the #1 overall pick. Or both!

There still might be some "slow down... no wait, speed up!" type of tactics. But the fun part here would be watching teams in the 1-6 range try to beat the hell out of each other in late-season games so they can attempt to push their opponents below the threshold and claim some of their ping pong ball combinations. Instead of Pacers-Nets or Jazz-Wizards being utter tank-offs, the Jazz might go, "Hey, the Wiz are 13.5 games back of Miami. If we beat them, it's more likely that some of their 140 shots at Darryn get redistributed to us." Washington would want to defend against that possibility and might actually try to (gasp) win the game.

Some teams would probably try to walk the line of losing the exact right number of games. But if they put themselves right on that cusp and then some other lottery team comes in and kicks them in the teeth in game 79 so they get some of their lottery odds, that would actually be an intriguing and hilarious thing to watch play out.

It's kind of a way to accomplish boosting the odds for 4, 5 and 6 at the expense of the absolutely terrible teams, but without just doing it outright. If nothing else, it would create some interesting dynamics in games that right now are mostly a contest of who can put more guys on the inactive list.

For what it's worth, last year two teams (Utah and NOP) finished 20+ games back of the playoff team with the worst record, and two others (Washington and Charlotte) finished at least 15 games behind. If four teams were trying a little bit harder, and if the 4-6 teams above them also wanted to hold them down for selfish reasons... wouldn't that lead to more interesting games?

Or frankly, just...

3. Go back to a less flat lottery

Could it work?: Look, flattening hasn't done what it was meant to do. They thought it would weaken the connection between being bad and landing Wemby, which it kind of did, but in the process they helped a bunch more teams to be ensorceled by the siren's song of a few more losses. Maybe it's just as simple as undoing the unintended consequences of the last "fix."

----

At the end of the day, the solution to tanking can't be to simply destroy competitive balance and make hope even more fleeting for the have-nots. It can't be just to entice other teams to tank instead.

The NBA is almost sure to try something, although anything they implement certainly won't impact this summer's draft. Hopefully whatever they land on won't create other unforeseen messes that are worse than the ones they're attempting to clean up.